Kelly Knievel's first motorcycle ride was as a day-old newborn in 1960, harnessed to his father Robert's back. According to family folklore, the then 22-year-old Robert – soon to be reinvented as fearless stunt-rider Evel Knievel – fishtailed his brand new Harley-Davidson returning home to the family trailer in Butte, Montana, from the maternity ward. He was so mortified by having endangered his firstborn that he sold the bike 24 hours later.

It's a revealing insight into the complex nature of a man who at his peak in the late 1970s was one of the most recognisable people on the planet, thanks to his self-publicised attempts to jump rattlesnakes, lions, rows of buses – and even canyons – on two wheels.

A born risk-taker, Knievel was also an inspirational father who led by example, sometimes at the expense of emotional intimacy, with his first wife, Linda, and their four children – Kelly, Robbie, Tracey and Alicia.

"I was incredibly proud of my dad," says Kelly, protectively clutching his late father's iconic stars and stripes crash helmet. "He was a one in a billion character who did everything in his life in the same bold, gigantic way that he jumped buses or cars or canyons.

"But his extraordinary ego and the self-confidence meant that he was an incredibly difficult and demanding person to be around. He was not a guy who talked about things … he was a guy who did things, and we learned by observation."

Born to German and Irish immigrant parents, Knievel was raised by his paternal grandparents following his parents' divorce, and after abortive attempts to carve out a career as a drill operator in a local mine and flirtations with ski-jumping and rodeo, plus short-lived spells as an unlicensed hunting guide and a semi-pro hockey player, he started to make an impact on the burgeoning motor-cross circuit.

By the time Kelly was seven, and following his father's spectacular failure to jump 12 cars and a cargo van in Montana the year before, which left him with several broken ribs and a shattered arm, the world was starting to take notice.

But it was Knievel's audacious attempt to jump a record-breaking 141 feet over the water fountains at Las Vegas's Caesars Palace on 31 December 1967 that lit the publicity touch paper.

"That's the first jump I really remember," says Kelly, mentally reliving the crash in which his father sustained a crushed pelvis and femur, fractures to his hip, wrist and ankles and concussion that left him in a coma for 30 days.

The seriousness of Knievel senior's injuries resulted in the notoriety, and the pulling power, he craved and he continued to up the ante – and his fees. For Kelly and his siblings, family life became a maelstrom of mixed emotions.

"There was never a time when I thought my dad wasn't like other dads. For us it was normal. But when we went out of town and everybody was taking your picture and we were thinking that we had to act a special way or be something or somebody other than who we really were, that was uncomfortable," he says.

"My brother Robbie, who is two years younger than me, wanted to be famous [Robbie is a successful daredevil himself, completing many of the jumps his father failed] and my dad loved the whole showmanship thing, but I just wasn't predisposed to fame."

Fear was also miraculously absent in the Knievel household. "I never once thought he was going to die," says Kelly. "Whenever Dad crashed, he would come home and heal up and he'd go back out and be Evel Knievel again.

"He was hurt a lot, but we never sat down as a family and discussed the possibility that he would die in a crash. Dad was 100% confident in everything he did in life. He had no doubts or fears, so making preparations for his death simply wasn't necessary."

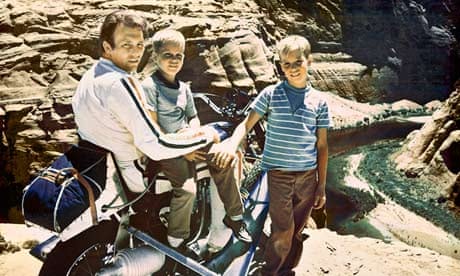

Kelly and his brother regularly accompanied their father at events, themselves performing on bikes for the huge crowds, but a knee injury kept him at home in the US for his father's infamous 1975 Wembley date, when he narrowly failed to clear 13 London buses in front of 90,000 spectators.

"I remember the phone call saying, 'Dad's crashed, but he's going to make it,' and that was that."

The family's itinerant lifestyle inevitably affected Kelly's education, but his father dealt with the protestations of his sons' Catholic schoolteachers with predictable impudence. "They called to say there were laws saying that his kids should be in school, and he just said, 'You know what? I think they're getting a better education with me than they're getting in that goddamn school.' Click."

Kelly collapses in laughter at the memory, but his father's indomitable confidence was a double-edged sword. "He overshadowed everybody. His ego was extraordinary but not in an arrogant way. He knew he was special, but he was mindful of the power of his personality. As a teenager, and even into my young adult life, that was very difficult," he admits.

"When I was growing up and developing my own personality, it was difficult to have a sense of my own identity because my identity was being the son of Evel Knievel, and that was kind of overpowering.

"And he didn't compartmentalise his life. There was no 'dad' role, no 'grandfather' role. He was just Evel Knievel, whether he was at the top of a ramp or sitting in his lounge chair.

"But as I got older, things worked themselves out," says Kelly, not completely convincingly.

Far from normal was the sudden wealth that Knievel's infectious bravado attracted. "Money wasn't his primary motivation," says Kelly, who now owns the intellectual property rights to the Knievel name and a huge collection of memorabilia, which is on tour in the UK, "but he sure loved to spend it. I'll never forget the day he came home in a Rolls-Royce in Butte, Montana. There was three feet of snow, and he was driving around town."

The family soon upgraded from their trailer to "one of the fanciest houses in Butte with eight acres of land and a lawn that took two days for us kids to cut," and Knievel's conspicuous consumption mushroomed.

"He bought us all Ferraris and clothes and jewellery, and always wanted the biggest and best of everything. He would start with a small boat, then a bigger boat, then an even bigger boat, and finally he'd end up with a yacht that had two boats on the side of it and a helicopter on the deck.

"He didn't fly the helicopter, but he learned to fly a plane. He started out with a Cessna and he ended up with Lear jets. At one time we had seven planes. He'd paint his name on the side of them."

But by 1980, just four years after he jumped seven Greyhound buses at the Seattle Kingdome in an emotional swansong, the money had evaporated.

"Every single penny," says Kelly. "We lost the big house to the bank in 1980, and the whole thing came down like a house of cards."

Precipitating the financial collapse was Knievel's 1977 conviction for assaulting his former promoter Shelly Saltman after he published a book alleging that Knievel was a drug user who abused his wife and children – claims that Kelly strongly denies.

The resulting six-month jail sentence contravened a clause in his contract with Ideal Toys – by then his biggest source of income via record-breaking action-figure sales – and, coupled with a crippling 1981 unpaid tax demand, left Knievel bankrupt.

Down but not out, Knievel Sr retreated from public life as interest – and his battered body – waned but, says Kelly, "his life never became a downward spiral."

By the time Knievel died in November 2007 from the progressive auto-immune condition pulmonary fibrosis, following a liver transplant, diabetes and decades of self-inflicted debilitating back trouble, he was a grandfather of 10, a great-grandfather of one, reunited with his estranged second wife, Krystal Kennedy.

But despite years of excruciating physical suffering, he remained defiant till the end. "He used to say he loved pain because he knew he wasn't dead yet," says Kelly. "He knew he was paying the price for the way he had lived his life, but there was no pity."

Today, Kelly – who runs a construction company in between overseeing the family legacy – lives with his wife and stepdaughter, a short jump away from Caesars Palace, scene of his father's breakthrough stunt and also his remarriage to Krystal.

"I don't need to see Caesars Palace to remind me of Dad," says Kelly, "but when I do think of him, and that's still every day, I appreciate him for being the character and the father he was and for helping me to understand human nature and the limits of what people are capable of."

For information about the Evel Knievel exhibition, visit facebook/evelknieveltour

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion