At the dawn of the 1990s, the nascent world wide web was a cluttered mess of simple text. It was hard to navigate, difficult to search, and nearly impossible for neophytes to enjoy. The first picture wasn't even uploaded to until 1992.

During these early days, a team of undergrad developers at the University of Illinois, led by 21-year-old wunderkind Marc Andreessen, looked to change all of that. “The original idea was how to [make] all of this information easily accessible to anyone,” says Eric Bina, one of the Illinois programmers.

By 1994, they had done exactly that.

On the 25th anniversary of Mosaic Communication Corporation's founding, the company that would eventually create Netscape Navigator, this is the story of how a browser became a symbol of the early web, and how, just as quickly, it became lost in its long search history.

The Browser Is Born

In 1992, Andreessen was a gifted Unix coder making $6.85 an hour at the university’s National Center for Supercomputing Applications. That’s where Andreessen (who declined to be interviewed for this article) met fellow programmer Bina. “He gave me his sales pitch... on his vision of what the internet could be,” Bina says.

Andreessen wanted to democratize the world wide web and make it truly global. “He wanted people to have access to all of this information whenever they wanted to,” Bina says. “From a computer, anywhere, over a network.” Bina was instantly hooked, drawn in by the thought of the internet becoming an instantaneous encyclopedia. “Marc’s a very good salesman,” Bina says, “That’s probably true of anyone who is a visionary.”

Browsers, an software application used to locate and display webpages, did exist prior to 1993. These early web-surfing applications were sort of like index cards with tightly packed text information on a single page, and they only ran on certain platforms.

After the Illinois team launched Mosaic, it immediately became the web’s most popular browser because of its user-friendly design.

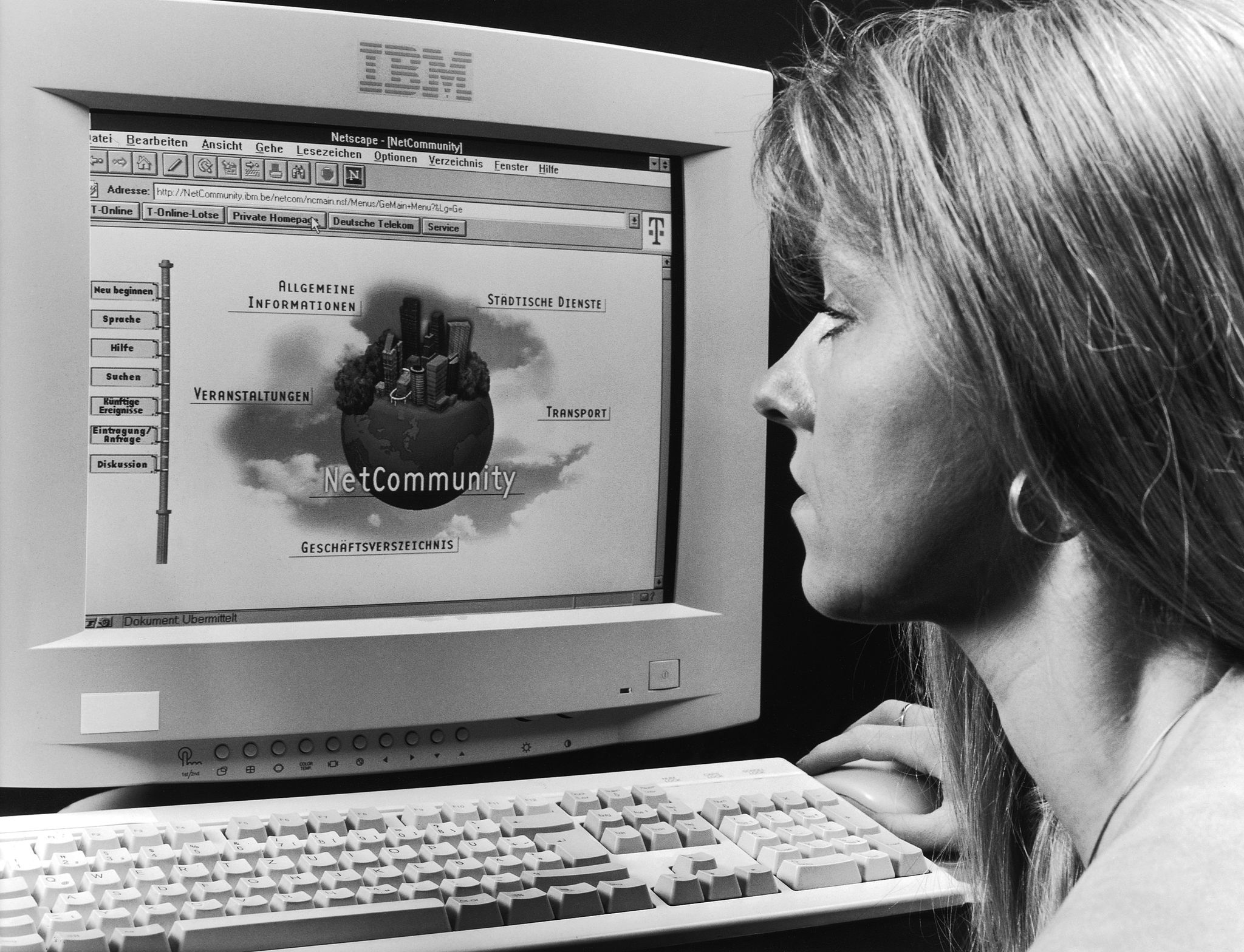

What made Bina’s and Andreessen’s creation so popular was that it did it in a “pleasurable” way, as described by Wired in 1994. Through the use of color photos, sound bites, video clips, and, most notably, hyperlinks, it made web browsing a point-and-click affair. Where there once was dull, blocky text, there was now eye-popping pixelated color photos.

“At the time, I [told Andreessen] that this was a terrible idea because it was going to break the internet. There just wasn’t enough bandwidth,” says Bina, “Of course, I was completely wrong.”

Mosaic would become the foundation for almost all web browsing.

Let’s Start Over and Do It Right

In January 1994, Jim Clark was wrapping up a career at iconic Silicon Graphics. Founded in 1981, the gaming and graphics workstation manufacturing company earned acclaim the previous summer for rendering the famed dinosaurs in Jurassic Park. On his final day at the office, he emailed Andreessen, who had graduated from college a month earlier. At the time, Clark was more interested in Andreessen’s talent than in Mosaic itself.

“Marc was keen not to do anything with Mosaic,” he says. “So, my next idea [was] related to online gaming. Like virtual reality games over a network.”

Andreessen and Clark approached Nintendo first. The Japanese gaming behemoth was on the cusp of announcing the new “Ultra 64,” known stateside as the Nintendo 64. Nintendo was interested, but wanted a large ownership stake in Clark and Andreessen's venture. So the two backed off.

Out of ideas, Andreessen recommended that they simply hire the Mosaic team, who were all graduating and needed jobs. Clark tells PM that he was initially skeptical, since it amounted to handing jobs to his partner’s friends. But they were talented programmers and had made a revolutionary web browser once. Why not try it again but better?

“[Mosaic] was a first draft anyway by a bunch of students,” Clark says. “So, let’s start over and do it right.”

On April 4, 1994, Clark and Andreessen formed Mosaic Communications Corporation. They ran into roadblocks almost immediately. For starters: The University of Illinois, where Bina and others still studied, held intellectual property rights to the original Mosaic as part of a university policy that’s still in effect today.

There was no way around it. The team had to start from scratch.

“I didn’t want a single line of code from [the original Mosaic], because that’s how we were going to stay out of court,” Clark says. Bina remembers: “We had to start from scratch and be ten times better. So, that was a challenge.”

Netscape Rising

That approach sounds smart, even noble. It didn’t work.

Despite their attempts not to run afoul of the university, Illinois sued the startup for intellectual property infringement. A December 1994 settlement forced Clark and Andreessen to pay millions and change the company name. They settled on “Netscape.”

“They tried to inhibit [us] instead of enabling us,” Clark says. “You should generate goodwill with students... who start companies. The proof are donations back to the school. Illinois blew it.”

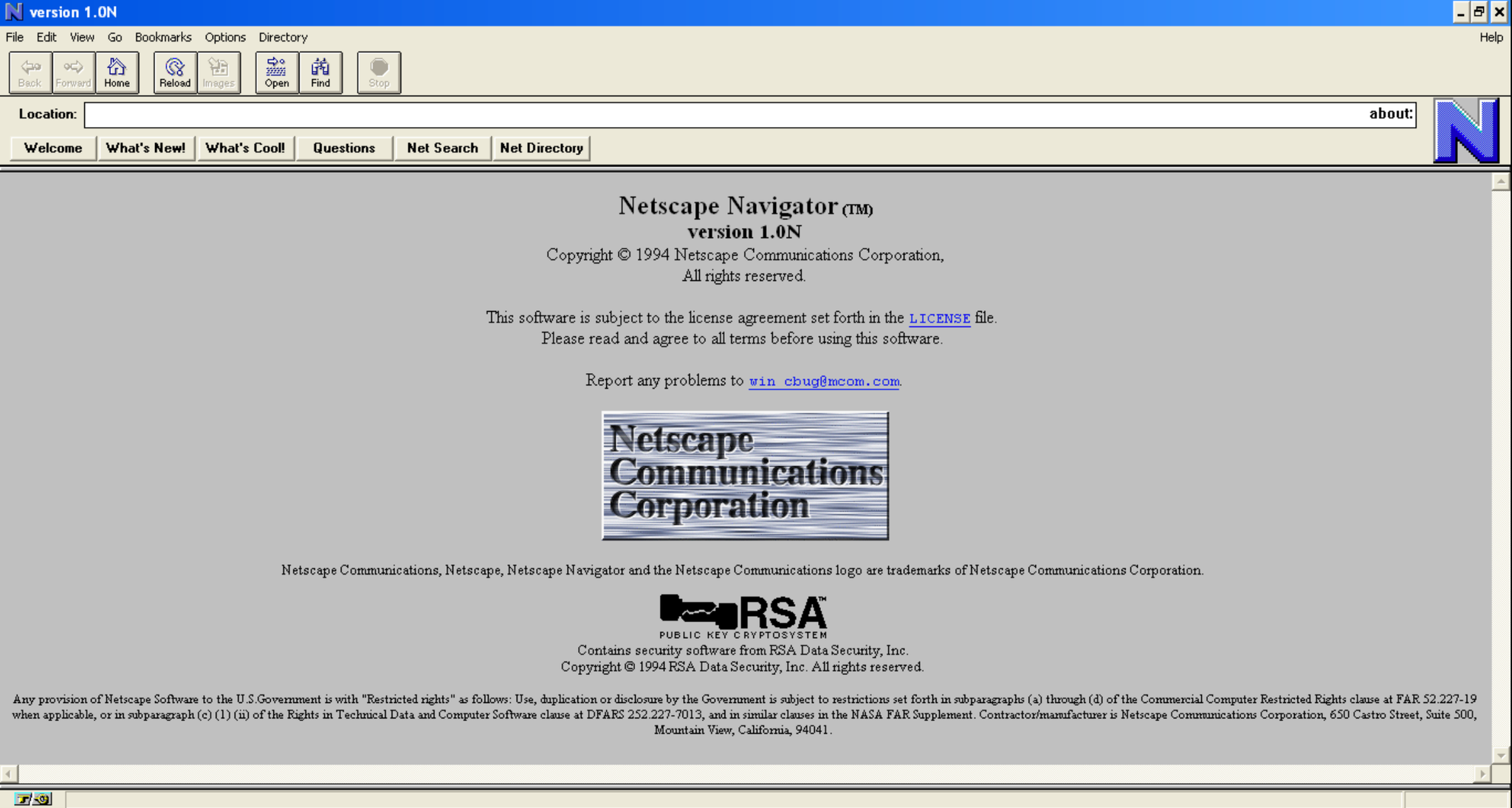

If the settlement was a low point, it came right before a crest. In mid-December 1994, the group released version 1.0, now known as Netscape Navigator. It was a massive success. Besides the interface’s point-and-click simplicity, Netscape also provided unprecedented security. Working with engineer Kipp Hickman, Netscape pioneered SSL (Secure Sockets Layer) Protocol. The technology established an encrypted link between browser and server, which allowed for privacy and consumer protection when submitting credit card numbers, stocks, or any other private information through the internet. The underlying technology of SSL still powers today’s security standard, TLS (Transport Layer Security).

“There needed to be an economic force driving [the internet], which meant that you had to be able to do business over the internet,” says Clark, “So, we created a secure way of doing transactions. It’s a bullet-proof rock solid way of authenticating two end points and having a secure connection. We invented that.”

The Year of Netscape

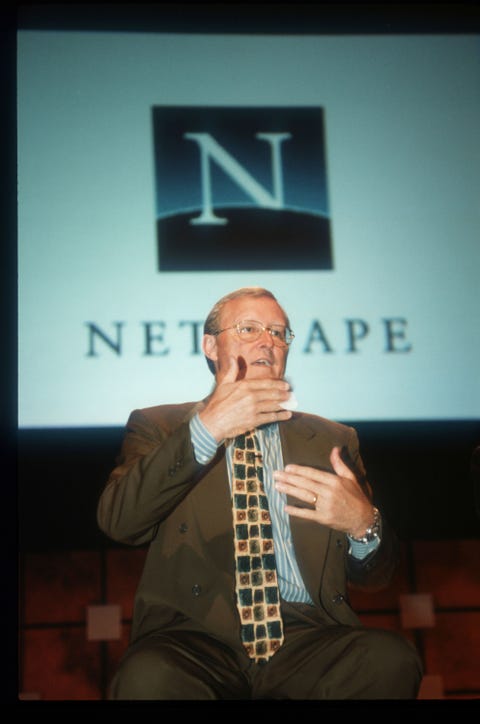

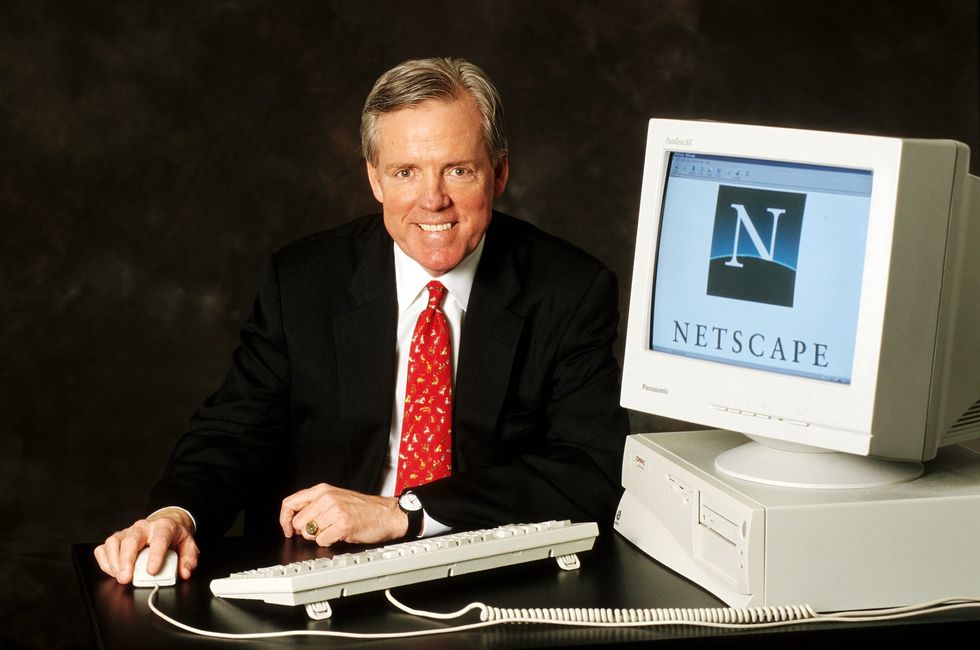

With the launch of Netscape Navigator, Jim Barksdale soon joined the company as CEO and immediately brought in huge investors like Hearst (Popular Mechanics’ parent company) and Times Mirror. Sales doubled in just a few months. According to Clark, there was even talk of a merger with Yahoo, another titan of the early internet.

In August 1995, Netscape went public. The company’s initial public offering set off a frenzy. At the time, The New York Times wrote that it was “one of the most stunning debuts in Wall Street history,” and The Wall Street Journal noted that “it had taken General Dynamics 43 years to be worth $2.7 billion in the stock market. It took Netscape about a minute.”

For the first time in history, Netscape proved that a company deeply embedded in the virtual world could be worth billions in the real one. The hype supercharged the dot-com bubble of the 90s and launched the internet age, creating today’s world where founders became instant nouveau riche on the day of their company's IPO.

But every huge coming out party needs a second act, so Netscape soon released version 2.0, which was faster, easier to use, incorporated Java applets, and allowed plug-ins so users could take advantage of other applications developed for the browser. This moment was Netscape’s zenith. It had millions of web users, 80 percent market share, and was valued in the billions. Fortune called the web browser’s rise “the beginning of the Internet age” and Andreessen was compared to Jim Morrison as he was called the web’s first true rock star.

As the calendar flipped to 1996, Netscape, and its visionary founder, were on top of the browser world, but they attracted the attention—and ire—of another tech giant.

Netscape may have boomed, but in 1995, it was Microsoft’s world. In June of that year, the story goes, Bill Gates’ behemoth allegedly proposed a deal, one that essentially would split up the web-browsing market between Netscape and Microsoft. Microsoft may have been hedging its bets against an upstart competitor, but Netscape saw the overture as an intimidation tactic. They refused the deal.

It was like a “visit by Don Corleone,” Andreessen would later say. “I expected to find a bloody computer monitor in my bed the next day.”

Two years later, Navigator would be facing extinction.

The Browser Wars

In August of 1995, days after Netscape’s debut as a publicly traded company, Microsoft launched Internet Explorer 1.0. Ironically, it was built on some of the same bones as Netscape Navigator.

Microsoft had licensed browser software from a company called Spyglass. Prior to that, Spyglass had brokered a deal with the University of Illinois to license Mosaic and its underlying technology, created at the university's National Center for Supercomputing Applications. Microsoft had found a willing partner in taking down Netscape.

“The university kept interfering with our business,” says Clark. “It also kept telling our potential customers that we were stealing their intellectual property.”

The fact that Microsoft was gunning for Netscape was no secret. A now-infamous internal memo from May 1995 highlights Gates’ mission to dethrone Netscape as the web’s de facto browser of choice. But Gates had an ace the startup couldn’t match: Bundling Internet Explorer with Microsoft’s ultra-popular operating system Windows 95.

So began the internet’s first “browser wars.” But this wasn’t a fair fight, Clark says—more “Red Wedding” than Godzilla vs. Mothra.

“It’s hard to be a start-up. We just couldn’t compete with Microsoft.” While Clark argues that his web browser was superior to Internet Explorer, to many web users, some logging on for the first time, the differences were negligible. The deciding factor was that Microsoft owned Windows 95.

Famously, Netscape and it backers also accused their Goliath rival of dirty tricks. In a recent Ringer article about the notorious 1998 antitrust lawsuit against Microsoft, the New York Attorney General’s Office antitrust bureau chief said Microsoft in the 90s applied pressure to various companies, including Apple, not to use Netscape. The article says that Microsoft employed strong-arm tactics “to smother Netscape in the cradle and cut off its air supply.”

While Barksdale and Clark brought convincing evidence in their case against Microsoft, the law doesn’t move at the speed of the fast-evolving tech business. It took until May 1998 for the U.S. Attorney General’s Office to pursue the antitrust case. By then, it was already too late for Netscape.

“We became the focus of a much more financially powerful company that had a huge monopoly advantage,” says Bina, “We faced the 800-pound gorilla and it stomped us into the dirt.”

Microsoft didn’t come out scot-free from its legal battle with the U.S. government. In 2000, it was determined that the company violated antitrust laws and exhibited predatory behavior, specifically towards to Netscape. Originally ordered to break up the multi-billion dollar company, a much lesser sentence was imposed that made it easier for browser competitors to integrate into Windows. Some said this amounted to little more than a slap on the company’s wrist.

Microsoft survived. Netscape didn’t.

By the fall of 1998, the deal was in place for AOL to acquire Netscape in their own effort to take on Microsoft. It would take two more decades, but they would lose, too.

One Company, Many Legacies

Netscape would hang on for another next decade before it finally pulled the plug on Navigator in December 2007—but the legacy of the web’s first big browser lives on.

Prior to being acquired by AOL, Andreessen publicly released the source code for Netscape Navigator 4.0, allowing a worldwide community of programmers to keep working on it. This effort would lead to the creation of Mozilla and its Firefox browser, one of the best alternatives to Google Chrome, the browser that would dethrone Internet Explorer in 2016.

Marc Andreessen is now a billionaire venture capitalist who was an early investor in Facebook and believes VR is the wave of the future. Jim Clark has leveraged his Netscape wealth to build other well-known startups such as Shutterfly and WebMD. Today, he’s working on several other projects, including a home and building automation system called CommandScape and doing away with something that we all use on the internet.

“We are trying to get rid of passwords,” says Clark, “by leveraging SSL and public key cryptography.”

Eric Bina decided to leave tech altogether. “I obsess over fruit trees,” he tells us from his Illinois home. He says he’s grown eleven different types of pawpaw trees from seed. “I entertain myself however I want to...I can do that because of Netscape.”

Navigator may be a relic buried in the internet’s browsing history, but Bina thinks Netscape’s true legacy lies in its vision to democratize the internet.

“Sometimes you do the right thing in the right place at the right time,” says Bina, “We gave lots of people access to all the cool things on the internet.”

Matt is a history, science, and travel writer who is always searching for the mysterious and hidden. He's written for Smithsonian Magazine, Washingtonian, Atlas Obscura, and Arlington Magazine. He calls Washington D.C. home and probably tells way too many cat jokes.